Fluid motions are quite complex and require rather advanced mathematics to describe them if all details are to be included. Simplifying assumptions can reduce the mathematics required, but even then the problems can get rather involved mathematically. To describe the motion of air around an airfoil, a tornado, or even water passing through a valve, the mathematics becomes quite sophisticated and is beyond the scope of an introductory course. We will, however, derive the equations needed to describe such motions, and make simplifying assumptions that will allow a number of problems of interest to be solved. These problems will include flow through a pipe and a channel, around rotating cylinders, and in a thin boundary layer near a flat wall. They will also include compressible flows involving simple geometries.

The pipes and channels will be straight and the walls perfectly flat. Fluids are all viscous, but often we can ignore the viscous effects. If viscous effects are to be included, we can demand that they behave in a linear fashion, a good assumption for water and air. Compressibility effects can also be ignored for low velocities such as those encountered in wind motions (including hurricanes) and flows around airfoils at speeds below about 100 m/s (220 mph).

In this chapter we will describe fluid motion in general, classify the different types of fluid motion, and also introduce the famous Bernoulli’s equation along with its numerous assumptions.

Motion of a group of particles can be thought of in two basic ways: focus can be on an individual particle, such as following a particular car on a highway (a police patrol car may do this while moving with traffic), or it can be at a particular location as the cars move by (a patrol car sitting along the highway does this). When analyzed correctly, the solution to a problem would be the same using either approach (if you’re speeding, you’ll get a ticket from either patrol car).

When solving a problem involving a single object, such as in a dynamics course, focus is always on the particular object: the Lagrangian description of motion. It is quite difficult to use this description in a fluid flow where there are so many particles. Let’s consider a second way to describe a fluid motion.

At a general point (x, y, z) in a flow, the fluid moves with a velocity V(x, y, z, t).

The rate of change of the velocity of the fluid as it passes the point is ∂ V/∂ t, ∂ V/∂ y,

∂ V/∂ z, and it may also change with time at the point: ∂ V/∂ t. We use partial derivatives here since the velocity is a function of all four variables. This is the Eulerian description of motion, the description used in our study of fluids. We have used rectangular coordinates here but other coordinate systems, such as cylindrical coordinates, can also be used. The region of interest is referred to as a flow field and the velocity in that flow field is often referred to as the velocity field. The flow field could be the inside of a pipe, the region around a turbine blade, or the water in a washing machine.

If the quantities of interest using the Eulerian description were not dependent on time t, we would have a steady flow; the flow variables would depend only on the space coordinates. For such a flow,

to list a few. In the above partial derivatives, it is assumed that the space coordinates remain fixed; we are observing the flow at a fixed point. If we followed a particular particle, as in a Lagrangian approach, the velocity of that particle would, in general, vary with time as it progressed through a flow field. But, using the Eulerian description, as in Eq. (3.1), time would not appear in the expressions for quantities in a steady flow, regardless of the geometry.

Three different lines can be defined in a description of a fluid flow. The locus of points traversed by a particular fluid particle is a pathline; it provides the history of the particle. A time exposure of an illuminated particle would show a pathline. A streakline is the line formed by all particles passing a given point in the flow; it would be a snapshot of illuminated particles passing a given point. A streamline is a line in a flow to which all velocity vectors are tangent at a given instant; we can- not actually photograph a streamline. The fact that the velocity is tangent to a streamline allows us to write

since V and dr are in the same direction, as shown in Fig. 3.1; recall that two vectors in the same direction have a cross product of zero.

In a steady flow, all three lines are coincident. So, if the flow is steady, we can photograph a pathline or a streakline and refer to such a line as a streamline. It is the streamline in which we have primary interest in our study of fluids.

A streamtube is a tube whose walls are streamlines. A pipe is a streamtube, as is a channel. We often sketch a streamtube in the interior of a flow for derivation purposes.

To make calculations for a fluid flow, such as forces, it is necessary to describe the motion in detail; the expression for the acceleration is usually needed. Consider a fluid particle having a velocity V(t) at an instant t, as shown in Fig. 3.2. At the next instant, t + Δ t, the particle will have velocity V(t + Δ t), as shown. The acceleration of the particle is

Figure 3.1 A streamline.

where (u, v, w) are the velocity components of the particle in the x-, y-, and z-directions, respectively, and i, j, and k are the unit vectors. For the particle at the point of inter- est, we have

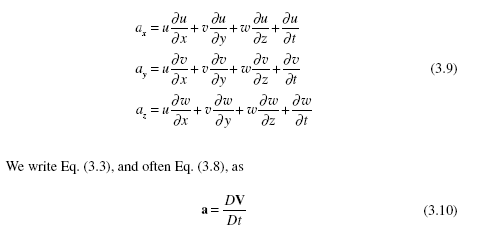

In Eq. (3.8), the time derivative of velocity represents the local acceleration and the other three terms represent the convective acceleration. Local acceleration results if the velocity changes with time (e.g., startup), whereas convective acceleration results if velocity changes with position (as occurs at a bend or in a valve).

It is important to note that the expressions for the acceleration have assumed an inertial reference frame, i.e., the reference frame is not accelerating. It is assumed that a reference frame attached to the earth has negligible acceleration for problems of interest in this book. If a reference frame is attached to, say, a dishwasher spray arm, additional acceleration components, such as the Coriolis acceleration, enter the expression for the acceleration vector.

The vector equation (3.8) can be written as the three scalar equations:

It can be used with other quantities of interest, such as the pressure: Dp/Dt would represent the rate of change of pressure of a fluid particle at some point (x, y, z).

The material derivative and acceleration components are presented for cylindrical and spherical coordinates in Table 3.1 at the end of this section.

Visualize a fluid flow as the motion of a collection of fluid elements that deform and rotate as they travel along. At some instant in time, we could think of all the elements that make up the flow as being little cubes. If the cubes simply deform and don’t rotate, we refer to the flow, or a region of the flow, as an irrotational flow.

We are interested in such flows in our study of fluids; they exist in tornados away from the “eye” and in the flow away from the surfaces of airfoils and automobiles. If the cubes do rotate, they possess vorticity. Let’s derive the equations that allow us to determine if a flow is irrotational or if it possesses vorticity.

Consider the rectangular face of an infinitesimal volume shown in Fig. 3.3. The angular velocity Ω about the z-axis is the average of the angular velocity of segments AB and AC, counterclockwise taken as positive:

These three components of the angular velocity represent the rate at which a fluid particle rotates about each of the coordinate axes. The expression for Ω2 would predict the rate at which a cork would rotate in the xy-surface of the flow of water in a channel.

The vorticity vector w is defined as twice the angular velocity vector: w = 2Ω. The vorticity components are

EXAMPLE 3.1

A velocity field in a plane flow is given by V = 2yti + xj. Find the equation of the streamline passing through (4, 2) at t = 2.

Solution

Equation (3.2) can be written in the form

The constant is evaluated at the point (4, 2) to be C = 0. So, the equation of the streamline is

Distance is usually measured in meters and time in seconds so that velocity would have units of m/s.

For the velocity field V = 2xyi + 4tz2 j − yzk, find the acceleration, the angular velocity about the z-axis, and the vorticity vector at the point (2, −1, 1) at t = 2.

Solution

The acceleration is found, using u = 2xy, v = 4tz2 , and w = − yz, as follows:

he angular velocity component Ωz is

ω = (−1 − 16)i − 4k = −17i − 4k

Distance is usually measured in meters and time in seconds. Thus, angular velocity and vorticity would have units of m/s/m, i.e., rad/s.

Labels: Fluid mechanics