Fluid mechanics is encountered in almost every area of our physical lives. Blood flows through our veins and arteries, a ship moves through water, airplanes fly in the air, air flows around wind machines, air is compressed in a compressor, steam flows around turbine blades, a dam holds back water, air is heated and cooled in our homes, and computers require air to cool components. All engineering disciplines require some expertise in the area of fluid mechanics.

In this book we will solve problems involving relatively simple geometries, such as flow through a pipe or a channel, and flow around spheres and cylinders. But first, we will begin by making calculations in fluids at rest, the subject of fluid statics.

The math required to solve the problems included in this book is primarily calculus, but some differential equations will be solved. The more complicated flows that usually are the result of more complicated geometries will not be presented.

In this first chapter, the basic information needed in our study will be presented.

Fluid mechanics is involved with physical quantities that have dimensions and units. The nine basic dimensions are mass, length, time, temperature, amount of a substance, electric current, luminous intensity, plane angle, and solid angle. All other quantities can be expressed in terms of these basic dimensions; for example, force can be expressed using Newton’s second law as

F = ma (1.1)

In terms of dimensions we can write (note that F is used both as a variable and as a dimension)

where F, M, L, and T are the dimensions of force, mass, length, and time. We see that force can be written in terms of mass, length, and time. We could, of course, write

Units are introduced into the above relationships if we observe that it takes 1 newton to accelerate 1 kilogram at 1 meter per second squared, i.e.,

This relationship will be used often in our study of fluids. In the SI system, mass will always be expressed in kilograms, and force in newtons. Since weight is a force, it is measured in newtons, never kilograms. The relationship

W = mg (1.5)

is used to calculate the weight in newtons given the mass in kilograms, and g =9.81 m/s2. Gravity is essentially constant on the earth’s surface varying from 9.77 m/s2 on the highest mountain to 9.83 m/s2 in the deepest ocean trench.

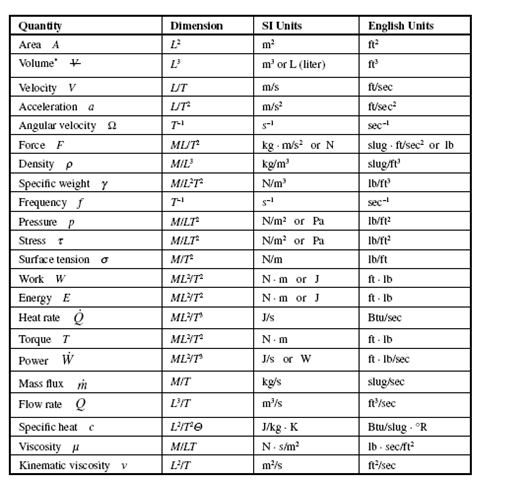

Five of the nine basic dimensions and their units are included in Table 1.1; derived units of interest in our study of fluid mechanics are included in Table 1.2. Prefixes

Table 1.1 Basic Dimensions and Their Units

| Quantity | Dimension | SI Units | English Units |

| Length l | L | meter m | foot ft |

| Mass m | M | kilogram kg | slug slug |

| Time t | T | second s | second sec |

| Temperature T | Q | kelvin K | Rankine R |

| Plane angle | radian rad | radian rad |

Table 1.2 Derived Dimensions and Their Units

are common in the SI system, so they are presented in Table 1.3. Note that the SI system is a special metric system. In our study we will use the units presented in these tables. We often use scientific notation, such as 3 × 105 N rather than 300 kN; either form is acceptable.

We finish this section with comments on significant figures. In almost every calculation, a material property is involved. Material properties are seldom known to four significant figures and often only to three. So, it is not appropriate to express answers to five or six significant figures. Our calculations are only as accurate as the least accurate number in our equations. For example, we use gravity as 9.81 m/s2, only three significant figures. It is usually acceptable to express answers using four significant figures, but not five or six. The use of calculators may even provide eight. The engineer does not, in general, work with five or six significant figures. Note that if the leading digit in an answer is 1, it does not count as a significant figure, e.g., 12.48 has three significant figures.

EXAMPLE 1.1

Calculate the force needed to provide an initial upward acceleration of 40 m/s2 to a 0.4-kg rocket.

Solution

Forces are summed in the vertical y-direction:

Note that a calculator would provide 19.924 N, which contains four significant figures (the leading 1 doesn’t count). Since gravity contained three significant figures, the 4 was dropped.

The substance of interest in our study of fluid mechanics is a gas or a liquid. We restrict ourselves to those liquids that move under the action of a shear stress, no matter how small that shearing stress may be. All gases move under the action of a shearing stress but there are certain substances, like ketchup, that do not move until the shear becomes sufficiently large; such substances are included in the subject of rheology and are not presented in this book.

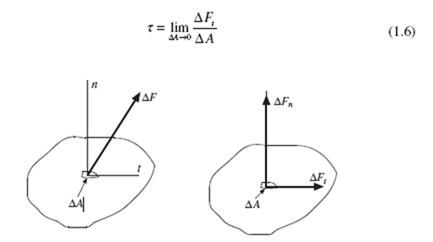

A force acting on an area is displayed in Fig. 1.1. A stress vector t is the force vector divided by the area upon which it acts. The normal stress acts normal to the area and the shear stress acts tangent to the area. It is this shear stress that results in fluid motions. Our experience of a small force parallel to the water on a rather large boat confirms that any small shear causes motion. This shear stress is calculated with

Each fluid considered in our study is continuously distributed throughout a region of interest, that is, each fluid is a continuum. A liquid is obviously a continuum but each gas we consider is also assumed to be a continuum; the molecules are sufficiently close to one another so as to constitute a continuum. To determine if the molecules are sufficiently close, we use the mean free path, the average distance a molecule travels before it collides with a neighboring molecule. If the mean free path is small compared to a characteristic dimension of a device, the continuum assumption is reasonable. At high elevations, the continuum assumption is not reasonable and the theory of rarified gas dynamics is needed.

If a fluid is a continuum, the density can be defined as

where Δ m is the infinitesimal mass contained in the infinitesimal volume Δ V . Actually, the infinitesimal volume cannot be allowed to shrink to zero since near zero there would be few molecules in the small volume; a small volume e would be needed as the limit in Eq. (1.7) for the definition to be acceptable. This is not a problem for most engineering applications, since there are 2.7×1016 molecules in a cubic millimeter of air at standard conditions. With the continuum assumption, quantities of interest are assumed to be defined at all points in a specified region. For example, the density is a continuous function of x, y, z, and t, i.e., ρ = ρ(x, y, z,t).

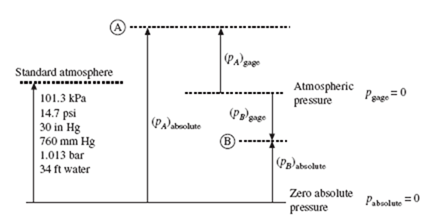

In our study of fluid mechanics, we often encounter pressure. It results from com- pressive forces acting on an area. In Fig. 1.2, the infinitesimal force Δ Fn acting on the infinitesimal area Δ A gives rise to the pressure, defined by

We can use p = ρgh to convert the units, where r is the density of the fluid with height h.

Pressure measured relative to atmospheric pressure is called gage pressure; it is what a gage measures if the gage reads zero before being used to measure the pressure. Absolute pressure is zero in a volume that is void of molecules, an ideal vacuum. Absolute pressure is related to gage pressure by the equation

where patmosphere is atmosphere is the atmospheric pressure at the location where the pressure measurement is made. This atmospheric pressure varies considerably with elevation and is given in Table C.3. For example, at the top of Pikes Peak in Colorado, it is about 60 kPa. If neither the atmospheric pressure nor elevation are given, we will assume standard conditions and use patmosphere = 100 kPa. Figure 1.3 presents a graphic description of the relationship between absolute and gage pressure. Several common representations of the standard atmosphere (at 40° latitude at sea level) are included in that figure.

We often refer to a negative pressure, as at B in Fig. 1.3, as a vacuum; it is either a negative pressure or a vacuum. A pressure is always assumed to be a gage pressure unless otherwise stated. (In thermodynamics the pressure is assumed to be absolute.) A pressure of −30 kPa could be stated as 70 kPa absolute or a vacuum of 30 kPa, assuming atmospheric pressure to be 100 kPa (note that the difference between 101.3 kPa and 100 kPa is only 1.3 kPa, a 1.3% error, within engineering acceptability).

We do not define temperature (it requires molecular theory for a definition) but simply state that we use two scales: the Celsius scale and the Fahrenheit scale. The absolute scale when using temperature in degrees Celsius is the kelvin (K) scale. We use the conversion:

In engineering problems we use the number 273, which allows for acceptable accu- racy. Note that we do not use the degree symbol when expressing the temperature in degrees kelvin nor do we capitalize the word “kelvin.” We read “100 K” as 100 kelvins in the SI system.

EXAMPLE 1.2

A pressure is measured to be a vacuum of 23 kPa at a location in Wyoming where the elevation is 3000 m. What is the absolute pressure?

Solution

Use Table C.3 to find the atmospheric pressure at 3000 m. We use a linear inter- polation to find patmosphere = 70.6 kPa. Then

The vacuum of 23 kPa was expressed as −23 kPa in the equation.

Labels: Fluid mechanics