Many, if not most, of the quantities of interest in fluid mechanics are integral quantities; they are found by integrating some property of interest over an area or a volume. Many times the property is essentially constant so the integration is easily performed but other times, the property varies over the area or volume, and the required integration may be quite difficult. Some of the integral quantities of interest are: the rate of flow through a pipe, the kinetic energy in the wind approaching a wind machine, the power generated by the blade of a turbine, and the drag on an airfoil. There are quantities that are not integral in nature, such as the minimum pressure on a body or the point of separation on an airfoil; such quantities will be considered in Chap. 5.

To perform an integration over an area or a volume, it is necessary that the integrand be known. The integrand must either be given or information must be avail- able so that it can be approximated with an acceptable degree of accuracy. There are numerous integrands where acceptable approximations cannot be made requiring the solutions of differential equations to provide the required relationships; external

flow calculations, such as the lift and drag on an airfoil, often fall into this category. In this chapter, only those problems that involve integral quantities with integrands that are given or that can be approximated will be considered.

4.1 System-to-Control-Volume Transformation

The three basic laws that are of interest in fluid mechanics are often referred to as the conservation of mass, energy, and momentum. The last two are more specifically called the first law of thermodynamics and Newton’s second law. Each of these laws is expressed using a Lagrangian description of motion; they apply to a specified mass of the fluid. They are stated as follows:

Mass: The mass of a system remains constant.

Energy: The rate of heat transfer to a system minus the work rate done by a system equals the rate of change of the energy E of the system.

Momentum: The resultant force acting on a system equals the rate of momentum change of the system.

Each of these laws applies to a collection of fluid particles and the density, specific energy, and velocity can vary from point to point in the volume of interest. Using the material derivative and integration over the volume, the laws are now expressed in mathematical terms:

where the dot over Q and W signifies a time rate and e is the specific energy included in the parentheses of Eq. (1.33). It is very difficult to apply the above equations directly to a collection of fluid particles as the fluid moves along in a simple pipe flow as well as in a more complicated flow, such as flow through a turbine. So, let’s convert these integrals that are expressed using a Lagrangian description to integrals expressed using a Eulerian description (see Sec. 3.1). This is a rather tedious

derivation but an important one. In this derivation, it is necessary to differentiate between two volumes: a control volume that, in this book is a fixed volume in space, and a system that is a specified collection of fluid particles. Figure 4.1 illustrates the difference between these two volumes. It represents a general fixed volume in space through which a fluid is flowing; the volumes are shown at time t and at a slightly later time t + Δt. Let’s select the energy E = ∫sys eρd V with which to demonstrate the material derivative. We then write, assuming Δt to be a small quantity,

where we have simply added and subtracted E1 (t + Δt) in the last line. Note that the

first ratio in the last line above refers to the control volume so that

where an ordinary derivative is used since we are no longer following a specified fluid mass. Also, we have used “c.v.” to denote the control volume. The last ratio in

Eq. (4.4) results from fluid flowing into volume 3 and out of volume 1. Consider the differential volumes shown in Fig. 4.1 and displayed with more detail in Fig. 4.2.

Note that the area A1+ A3 completely surrounds the control volume so that

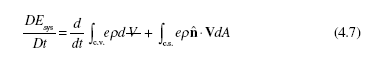

where “c.s.” is the control surface that surrounds the control volume. Substituting Eqs. (4.5) and (4.6) into Eq. (4.4) results in the Reynolds transport theorem, a system- to-control-volume transformation:

If we return to the energy equation of Eq. (4.2) we can now write it as

If we let e = 1 in Eq. (4.7) [see Eq. (4.1)], the conservation of mass results. It is

And finally, if we replace e in Eq. (4.7) with the vector V [see Eq. (4.3)], Newton’s second law results:

These three equations can be written in a slightly different form by recognizing that a fixed control volume has been assumed. That means that the limits of the first integral on the right-hand side of each equation are independent of time. Hence, the time derivative can be moved inside the integral if desired. Note that it would be written as a partial derivative should it be moved inside the integral since the integrand depends, in general, on x, y, z, and t. For example, the momentum equation would take the form

The following three sections will apply these integral forms of the basic laws to problems in which the integrands are given or in which they can be assumed.

4.2 Continuity Equation

The most general relationship for the conservation of mass using the Eulerian description that focuses on a fixed volume was developed in the preceding section as Eq. (4.9). Since the limits on the volume integral do not depend on time, this can be written as

If the flow of interest can be assumed to be a steady flow so that time does not enter the above equation, the equation simplifies to

Those flows in which the density r is uniform over an area are of particular interest in our study of fluids. Also, most applications have one entrance and one exit. For such a problem, the above equation can then be written as

where an over bar denotes an average over an area, i.e., VA = ∫VdA. Note also that

at an entrance we use nˆ ⋅ V1 = −V1 since the unit vector points out of the volume, and the velocity is into the volume. But at an exit, nˆ ⋅ V2 = V2 since the two vectors are in the same direction.

For incompressible flows in which the density does not change1 between the entrance and the exit, and the velocity is uniform over each area, the conservation of mass takes the simplified form:

We refer Eqs. (4.12) to (4.15) as the continuity equation. These equations are used most often to relate the velocities between sections.

The quantity rAV is the mass flux and has units of kg/s. The quantity VA is the flow rate (or discharge) and has units of m3/s. The mass flux is usually used in a gas flow and the discharge in a liquid flow. They are defined by

where V is the average velocity at a section of the flow.

EXAMPLE 4.1

Water flows in a 6-cm-diameter pipe with a flow rate of 0.02 m3/s. The pipe is reduced in diameter to 2.8 cm. Calculate the maximum velocity in the pipe. Also calculate the mass flux. Assume uniform velocity profiles.

Solution

The maximum velocity in the pipe will be where the diameter is the smallest. In the 2.8-cm diameter section we have

Water flows into a volume that contains a sponge with a flow rate of 0.02 m3/s. It exits the volume through two tubes, one 2 cm in diameter, and the other with a

mass flux of 10 kg/s. If the velocity out of the 2-cm-diameter tube is 15 m/s, determine the rate at which the mass is changing inside the volume.

Solution

The continuity equation (4.9) is used. It is written in the form

Labels: Fluid mechanics