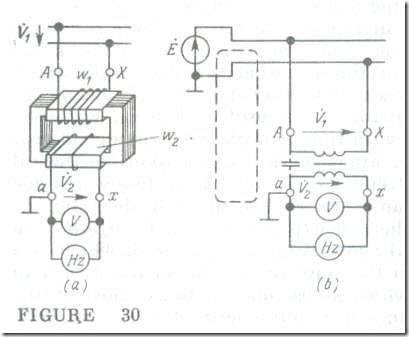

The Equivalent Circuit for a Phase of an Induction Motor

The Equivalent Circuit for a Phase of an Induction Motor In calculating the process taking place in an induction motor, resort is usually made to the equivalent circuit of one phase. This circuit is assumed to include fixed resistive and inductive elements and also a variable resistive element to represent the mechanical load applied to the motor shaft. The difficulties. in developing such an equivalent circuit arise because, firstly, the frequency of the stator phase currents is f and that of the rotor phase currents is f 2 = f s , secondly, the stator phase has w 1 turns and the rotor phase has w 2 turns, thirdly, the two windings differ in the winding factors k w 1 and k w 2 and fourthly, the stator has m l = 3 phases and a squirrel-cage rotor has m 2 = N phases. Therefore, all rotor phase quantities must be referred (or transferred) to the respective stator quantities. To begin with, we will refer the rotor phase quantities to the stator phase frequency. To this...